How do you survive in a society you are not built for?

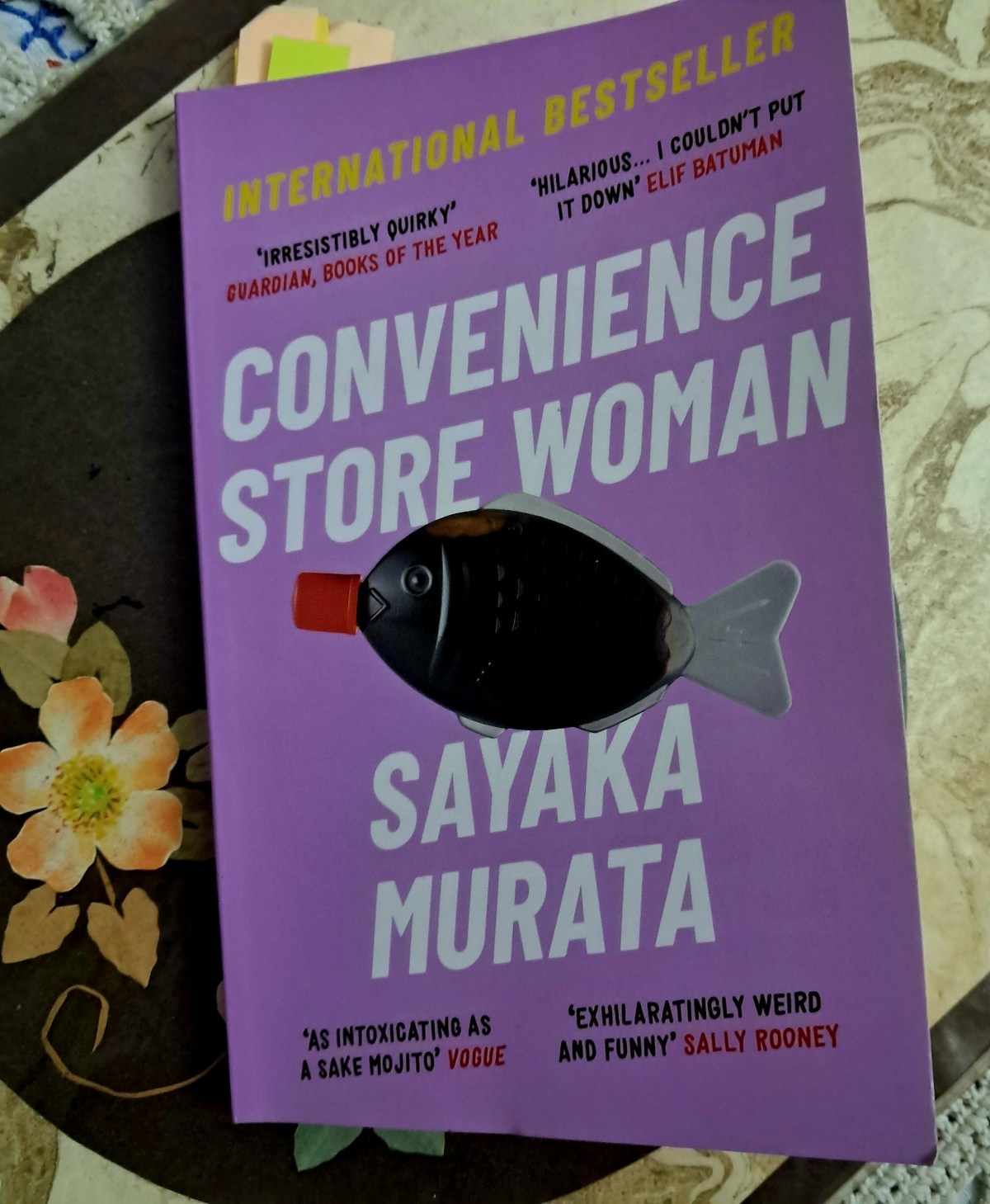

Convenience Store Woman (2018) by Japanese author Sayaka Murata (trans. Ginny Tapley Takemori) takes this question head on. This is a short, slim and extremely readable novel with a racy style and an aestheticised deadpan humour (so Japanese!) and is quite bewildering. This novel is a first-person account of a 36-year old woman Keiko Furukura who has been working part-time in the same convenience store in modern-day Tokyo for 18 years. The writer herself also worked at a convenience store for 18 years until this novel brought her fame and allowed her to pursue writing full-time.

Keiko has always been different. Her parents try to ‘cure’ her, her sister comes up with excuses she can use in socially-awkward situations in order to help her come across as an emotionally intelligent human. Keiko learns that keeping “her mouth shut was the most sensible approach to getting by in life” and grows into adulthood as the epitome of a self-effacing people-pleaser. She observes, astutely analysing, commenting and adopting the script of ‘normal’ people in order to survive. Some of her insights are trenchant remarks on the behaviour around her: “I’d noticed soon after starting the job that whenever I got angry at the same things as everyone else, they all seemed happy…I pulled off being a person” or “When something was strange, everyone thought they had the right to come stomping in all over your life to figure out why. I found that arrogant and infuriating, not to mention a pain in the neck” or that being an adult meant “having crow’s feet, talking in a more relaxed manner, and wearing monotone clothes” or that “the normal world has no room for exceptions and always quietly eliminates foreign objects. Anyone who is lacking is disposed of.”

“The truth that is beyond what people read as the truth. The real truth that is hidden under a lid and has not yet become words. I’ve wanted to see this ever since I was a child. [..] When I write my stories I am being pulled around by them. I never know where the story will take me. Someday I want to get to what is deep down in people. Not so much what people believe to be- but rather something you try not to see. Something that will be dangerous to put into words.”

Sayaka Murata

The Convenience Store as a Haven of Humdrum

The convenience store offers Keiko a controlled environment in which you just wear a uniform and do as the manual says. “As long as you wear the skin of what’s considered an ordinary person and follow the manual, you won’t be driven out of the village or treated as a burden. You play the part of the fictitious creature called ‘an ordinary person’ that everyone has in them. Just like everyone in the convenience store is playing the part of the fictitious creature called ‘a store worker’.” Belonging becomes her biggest sense of achievement as she takes pride in being ‘a cog in society.’

Murata’s work has struck a deep chord with sexual minority groups and ‘divergent’ communities who have found solace in her work and the way that it describes their everyday struggle to conform to society’s long list of expectations from gender roles, status, marriage, to ideas of success and the well-lived life. Although several reviewers have also talked about Keiko’s neurodivergent tendency in misreading social cues and her learned behaviour in order to survive and how that relates to the challenges of conditions like autism or ADHD, the novel does not explicitly address these. A perspective that isn’t sufficiently discussed is that of Keiko’s struggles and lived experience as a single woman in her late 30s navigating a society in which “you have no value unless you are married or have a career.” Keiko is a woman without the ambition to move up the social ladder or to reach life goals such as marriage or kids and finds her ultimate purpose and fulfillment in the familiar and comforting space of a convenience store as that seems to be the only thing she can do, and do very well. Her entire character arc goes from being an incorrigible people-pleaser, absorbing speech cadences, dressing and make-up styles from those around her to having her own epiphany: “I realize now more than a person, I’m a convenience store worker. Even if that means I’m abnormal and can’t make a living and drop down dead, I can’t escape that fact. My very cells exist for the convenience store.”

Key themes and Insights

This is a novel that upends notions of selfhood, independence, empowerment and also resilience. Keiko’s quiet resilience in continuing to live her non-descript and mundane life that no one around her understands is valuable in itself for her. The author defies the reader to judge her, to feel sorry for her and to pity her only to realise that there is more than meets the eye. In her cheat codes for survival, Keiko is smarter than we care to acknowledge and has the courage to embrace the only path that is truly available to her. Is this also not what the stoics tell us to do? Even if this path of individuality is to be found at the alter of robotic consumerism. In this web of contradictions, is this obsession with the convenience store an ode to modernity? Is Keiko, after all, the ideal worker in a capitalist system as she eats, keeps her body fit and gets enough sleep only to be able to work again? Or is she a woman who chooses to remain in the safety of an environment she can fit in to survive in a society that she isn’t built for? The only truth that Murata seems to hint at is that unlike everything else, resilience does not have a script. It is not always loud and can also exist in this way- invisible, light-footed, compliant yet non-conforming.